Iñaki Permanyer and Júlia Almeida Calazans

Policymakers and scholars are increasingly interested in monitoring and curbing health inequalities. Much is known about the main causes of death and how mortality has been shifting from most deaths around the world being caused by communicable diseases towards most being due to non-communicable causes.

However, less is known about the heterogeneity in these causes of death. Are people in some countries dying from an increasingly varied set of causes? Measuring how ‘similar’ or ‘dissimilar’ the different causes of death are can help us understand global health inequalities and patterns of mortality.

Assessing how heterogeneous causes of death are is important for several reasons. Different causes of death require different preventive actions and treatments, so if people in a population are dying from a greater number of causes, health systems must allocate their scarce resources to preventing a wider range of causes.

Understanding heterogeneity in causes of death also helps us understand the biological and social drivers of morbidity and mortality and develop better conceptual and explanatory models. This can throw considerable light on our understanding of contemporary health dynamics and the social determinants of health.

Previous research has tried to document how diverse a given cause of death profile is. These studies proposed measures to assess whether deaths are highly concentrated within a limited set of causes or are widely spread across many causes. They found that declines in deaths from cardiovascular causes in low-mortality countries (largely due to improvements in treatment) were followed by an increase in deaths from other chronic and degenerative diseases, thus diversifying the cause of death profile.

However, cause of death diversity doesn’t consider the extent of similarity or dissimilarity among causes of death. For example, ‘road injuries’ and ‘interpersonal violence’ are unrealistically assumed to be just as dissimilar as ‘road injuries’ and ‘Alzheimer’s disease’.

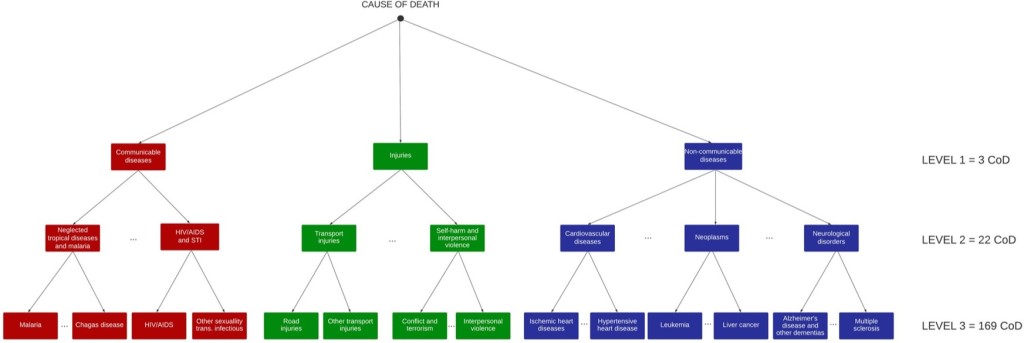

In our study, recently published in the IJE, we introduced a new measure – the cause of death inequality indicator – to assess the extent of dissimilarity among causes of death. This measure is defined as the average expected ‘dissimilarity between any two causes of death’. By definition, the cause of death inequality indicator has the lowest value of 0 whenever all individuals die from the exact same cause. Its value increases as individuals die from an increasingly varied set of causes. It is based on the length of the shortest path between two given causes of death in the tree-like diagrams that are often used to classify different causes of death, as seen in the example below.

Using this measure, two causes that are clustered together under an upper branch in this tree (like ‘road injuries’ and ‘interpersonal violence’) are deemed to be more similar than two causes that are further apart (like ‘road injuries’ and ‘Alzheimer’s disease’).

We tested this new inequality indicator and an existing diversity indicator for causes of death in several low-mortality countries. In doing so, we found that inequality and diversity measures for cause of death do not necessarily move in the same direction.

For example, between 1990 and 2019 in Finland, increases in cause of death diversity went hand in hand with decreases in cause of death inequality. As chronic and degenerative causes of death, especially neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, became more common, causes of death became more diverse and thus more unpredictable. However, as these causes of death are concentrated in the same branches of the classification tree, the deaths share similar aetiologies (e.g. they are all non-communicable causes), and cause of death inequality declines as a result.

Our findings therefore show that cause of death diversity and inequality indicators offer complementary information about the heterogeneity among causes of death.

It’s important to highlight that our illustration of this concept was done for countries with universal coverage and high levels of completeness of death records. Future research exploring the dynamics of cause of death inequality in other regions should bear in mind that the quality of the data source could be a limitation in estimating cause of death heterogeneity.

Despite this limitation, cause of death heterogeneity indicators can inform effective health policies and the promotion of social and preventive medicine, especially if used in conjunction with other population health indicators, such as life expectancy and lifespan inequality.

Read more:

Permanyer I, Calazans JA. On the measurement of cause of death inequality. Int J Epidemiol 2024; 14 February. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyae016

Iñaki Permanyer is an ICREA Research Professor at the Centre for Demographic Studies (CED), in the Autonomous University of Barcelona. He is the head of the Health and Aging Unit at CED and the PI of HEALIN, an ERC Consolidator Grant project (2020–2025). He has more than 50 publications in top field journals like Population and Development Review, PNAS, Demography, the Journal of Development Economics, World Development, and Demographic Research. His research focuses on the study of population health metrics and health inequalities.

Júlia Almeida Calazans is a postdoctoral researcher on the project ‘Healthy lifespan inequality: measurement, trends, and determinants’ at the CED. Her publications have featured in high-impact journals, including the Pan American Journal of Public Health, International Journal for Equity in Health, BMC Public Health, BMJ Open, and Demographic Research. Her main areas of interest are cause of death, mortality estimates, and demographic techniques.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) in relation to the research program ‘Healthy lifespan inequality: measurement, trends and determinants’, under grant no. 864616, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation R+D LONGHEALTH project (grant PID2021-128892OB-I00).