Cecilie Svanes, Jennifer Koplin, Francisco Gomez Real, and Svein Magne Skulstad

A new study shows that asthma is three times more common in those who had a father who smoked in adolescence, and twice as common in those whose father worked with welding before conception. Can these numbers be reduced by including adolescent boys in public health prevention programmes?

It is well known that a mother’s environment plays a key role in child health. The hypothesis that health and disease originate early in life has dramatically increased our understanding of this issue. However, recent research suggests that this may also be true for fathers; i.e. father’s lifestyle and age appear to be reflected in molecules that control gene function. There is growing evidence from animal studies for “epigenetic” inheritance, a mechanism whereby the father’s environment before conception could impact on the health of future generations.

In this innovative study, the researchers investigated whether parental exposure to smoking and welding influenced asthma risk in offspring, with a particular focus on exposures in fathers and exposures occurring before conception. The authors aimed to identify susceptible windows during sperm precursor cell development, by addressing whether potential preconception effects were related to exposure age, exposure duration, and time from quitting exposure until conception. More than 24,000 offspring from population-based cohorts in Denmark, Estonia, Iceland, Norway and Sweden were investigated.

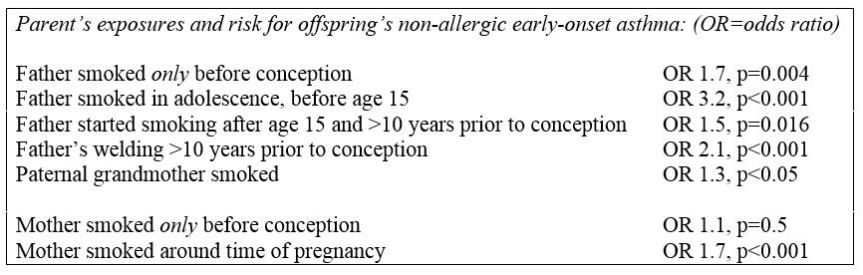

For the first time, this study demonstrates that individuals with a father who smoked but quit smoking before conception, were more likely to have asthma than those whose father never smoked or started smoking after their birth. Importantly, the greatest increase in risk for asthma in offspring was found for fathers who started smoking before age 15. A long duration of father’s smoking before conception also increased asthma in offspring. The findings were similar in all social classes and were pronounced for non-allergic early-onset asthma. Interestingly, starting smoking early was harmful even if the father quit smoking years before conception.

These are novel findings with potentially large impact, and in an attempt to replicate the concept the researchers addressed another exposure relevant in young men, namely welding – an occupational exposure. The analyses revealed that father’s welding before conception increased offspring asthma risk. This was independent of the smoking effects, and mutual adjustment did not alter the estimates of either. For welding (as for smoking) starting after puberty, exposure duration before conception appeared to be the most important determinant for their children’s asthma risk. Thus, the role of future fathers’ environment on offspring health was found for two different exposures – both smoking and welding.

Concerning mother’s smoking, this study observed a greater risk of offspring asthma if the mother smoked in pregnancy, consistent with previous literature. However, no effect was identified if the mother quit smoking prior to conception. This latter finding is novel and suggests differences in exposure effects through male and female germ cells.

Smoking is known to cause genetic and epigenetic damage to spermatozoa, transmissible to offspring and with potential to induce developmental abnormalities. Welding represents another complex exposure, also known to impact sperm with potential impact for subsequent generations. Laboratory models suggest three vulnerable time windows in the development of male germ cells:

- In utero, when grandmother smoking may influence primordial germ cell development.

- In prepuberty, when de-novo DNA methylation occurs during primordial germ cell differentiation into spermatogonia.

- After puberty, when spermatogonia multiply and develop into spermatocytes during reproductive cycles.

For the first time in humans, the study observed effects of exposure in each of these periods, with the strongest effects of exposure in 2: the early puberty period. Lab studies further show impaired DNA repair mechanisms in smoking exposed spermatozoa. A similar damage to spermatogonia could explain why fathers’ smoking was harmful for their children, even if they quit smoking years before conception.

This important new study provides an unexpectedly strong argument for focusing on the environment of young men in public health strategies. There is an urgent need for research that addresses other exposures in young men as well as for research exploring the mechanisms by which fathers’ pre-conception smoking and welding influence future children’s health.

Read more:

Svanes C, Koplin J, Skulstad SM, et al. Father’s environment before conception and asthma risk in his children: A multi-generation analysis of the Respiratory Health in Northern Europe study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016, doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw151 [Free to access until 30 November 2016].

Soubry A, Hoyo C, Jirtle RL, Murphy SK. A paternal environmental legacy: evidence for epigenetic inheritance through the male germ line. Bioessays 2014;36:359-71. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300113

Northstone K, Golding J, Davey Smith G, Miller LL, Pembrey M. Prepubertal start of father’s smoking and increased body fat in his sons: further characterisation of paternal transgenerational responses. Eur J Hum Genet 2014;22:1382-6. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.31.

Cecilie Svanes MD PhD is an internationally acknowledged expert in the field of early life origins of asthma, allergy and lung function. She works as a professor in international health and as a specialist in occupational pulmonary medicine.

Jennifer Koplin PhD is an early career fellow with expertise in the epidemiology of food allergy, working at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and the University of Melbourne School of Population and Global Health.

Francisco Gomez Real MD PhD is an international expert in reproductive and hormonal factors in respiratory health, with clinical background in obstetrics/gynaecology and in respiratory medicine.

Svein Magne Skulstad MD PhD is a postdoctoral fellow with expertise in fetal medicine, with clinical background from obstetrics/gynaecology and transfusion medicine and immunology.

I feel really happy to have seen your webpage and look forward to so many more asthma studies reading here. Thanks once more for all the details.

LikeLike

I enjoyed readingg your post

LikeLike